Sponge Parks: Porous Powerhouses for Climate Resilience

Written By: Ramya M. A.

Chennai’s future is closely tied to its waters. As climate change reshapes coastal cities worldwide, Tamil Nadu’s shoreline faces rising flood risks. 91% of its coastal area is predicted to face high flood risk by 2100. Chennai, a coastal city with an estimated current population of over 12 million, runs severe risk of heavy flooding. An early example of this was most notable during the devastating 2015 deluge, which caused an estimated USD 3 billion in damages.

Urban sprawl and land use planning are major factors that have increased the city’s susceptibility to floods. Since1980, over 150 water bodies have been encroached upon. Wetlands, which act as natural buffers against flooding, have declined drastically, from occupying an 80% share in the total land area in 1980 to just 15% in 2010.

Picture this; what if cities could act like sponges instead of concrete blocks?

This is where nature-based solutions like sponge parks factor in. Sponge parks are artificially engineered wetlands designed to absorb, filter, store and slowly release rainwater, mimicking the functions of the natural wetlands. They can play a vital role in water retention, flood protection, increasing green cover and reducing ambient temperatures. The word is derived from the term “Sponge cities”, first coined in China, which describes cities that are designed to retain and reuse stormwater by restoring natural waterways and integrating permeable green spaces within the urban fabric.

Chennai has opened its first wetland sponge park in Porur. Spanning 16.6 acres, the park was developed on the Open Space Reservation (OSR) land of Ramachandra University. As per the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA)’s mandate, 10% of land in any development over 10,000 square metres must be set aside as OSR. The site was formerly an asphalted parking lot and waste dumping ground, with no water permeability. Today, it functions as a natural water treatment system, using landscape and ecology to manage stormwater.

The Sponge Collaborative, a Chennai-based consulting, design, and planning firm that led the park’s design and implementation, recently organised a guided tour of the sponge park.

The journey of water through the sponge park is a multi-step process:

- Bioswale: Stormwater first flows into a bioswale—vegetated channels that slow down the flow of water, trap pollutants, and allow infiltration.

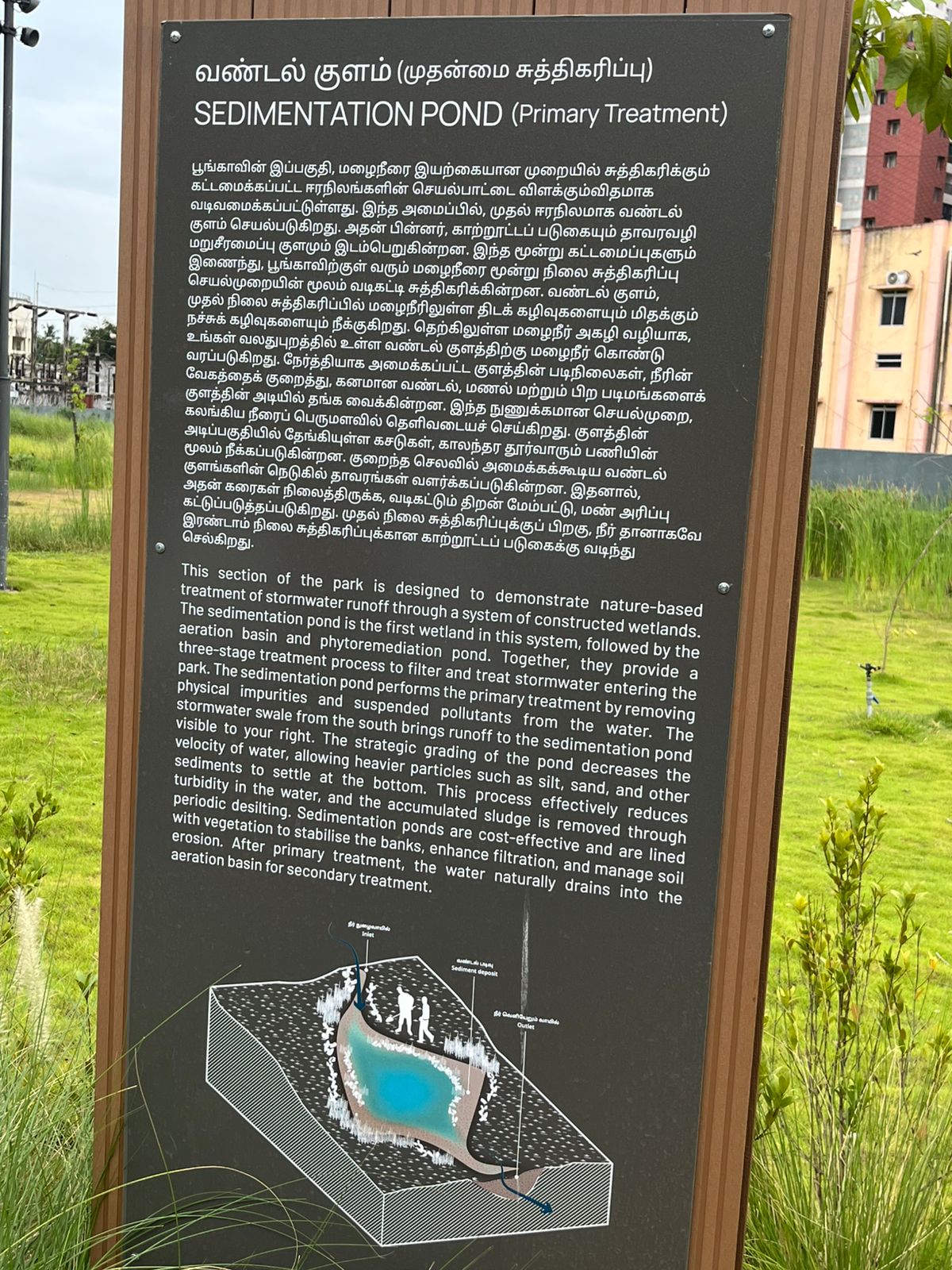

- Sedimentation Pond: Water then enters a pond where heavier particles settle at the bottom, removing initial silt and debris.

- Aeration Pond: Next, it is oxygenated using aquatic plants such as Cyperus and Lemongrass, improving water quality.

- Phytoremediation Pond: Specially selected plants help absorb nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from the water. While effective for nutrient removal, such systems have limitations in treating heavy metals, which require more advanced methods.

- Retention Basin: Finally, the treated water collects in a retention pond with a holding capacity of 30,000 litres, helping recharge groundwater and prevent urban flooding.

Key lessons from Chennai’s sponge park

The tour offered some interesting insights into the challenges of effective planning and implementation, and highlighted enabling factors that contributed to its success.

Procuring specific wetland plants and phytoremediation species proved difficult due to their unavailability in local nurseries and with suppliers. This issue was compounded by the fact that several special plant species required for the park were not included in the Horticulture Department’s Schedule of Rates, a government-issued document that standardises the costs of materials, labour, and equipment for infrastructure projects, making budgeting and procurement more complex.

Ensuring long-term financial sustainability remains a concern, as the park is freely accessible to the public. To address this, the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority is exploring Public-Private Partnerships and Corporate Social Responsibility funding models to secure resources for long-term maintenance. Additionally, capacity building trainings are needed for the maintenance personnel and ward-level officials to ensure they are adequately trained in regular maintenance and upkeep of the site.

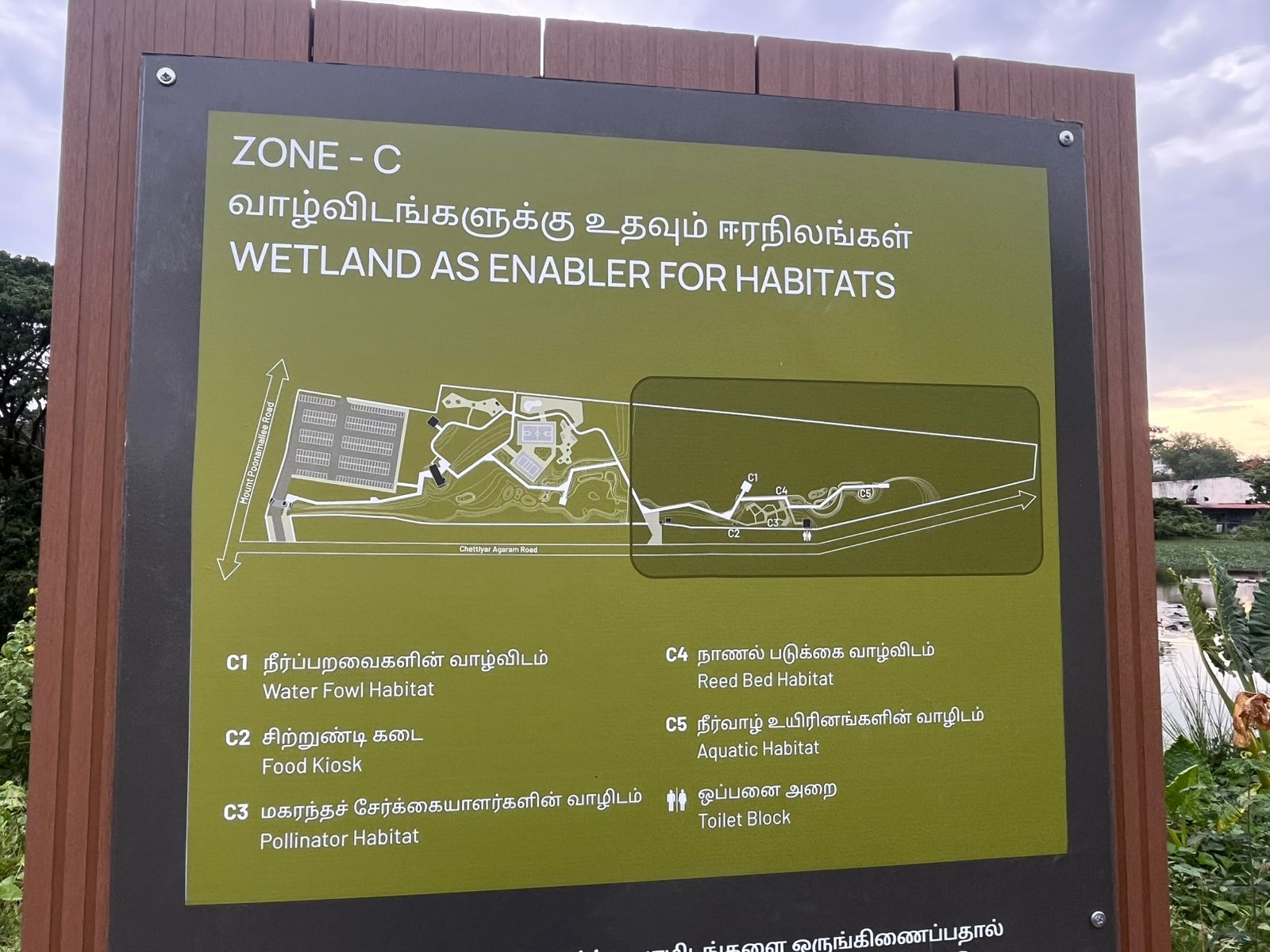

Several enabling factors contribute to the success of the park. Colourful and easy to understand signages, a play area, and a walking track attract active community engagement, making the space accessible and educational for all. This helps reinforce the importance of inclusivity in climate-adaptive urban design.

Future plans include monitoring and quantifying the park’s impact, particularly on parameters such as biodiversity, local temperature, air pollution, mental well-being and local flood reduction to provide the evidence base needed to guide replication and attract further investment in similar initiatives. Embedding such pilot initiatives and broader nature-based strategies into local development frameworks, including Chennai’s forthcoming Third Master Plan, is essential to ensure their long-term sustainability and city-wide adoption.

Chennai’s initiative demonstrates how with inclusive planning, ecological design, and long-term financing, sponge parks can serve as powerful tools for enhancing local climate resilience, by reducing urban flooding, recharging aquifers, lowering ambient temperatures, and simultaneously offering recreational spaces.

As climate risks intensify, it is imperative that cities reimagine how public spaces are planned and utilised, embedding climate-resilient and green infrastructure into spatial planning to build healthier and liveable urban futures.